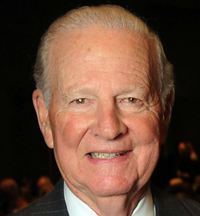

James A. Baker

James Baker served as Undersecretary of Commerce for President Gerald R. Ford and ran the President Ford’s 1976 campaign. He later served as White House Chief of Staff and Secretary of the Treasury under President Ronald Reagan. President George H.W. Bush appointed him as Secretary of State and later as White House Chief of Staff. He is a Trustee of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation.

James Baker served as Undersecretary of Commerce for President Gerald R. Ford and ran the President Ford’s 1976 campaign. He later served as White House Chief of Staff and Secretary of the Treasury under President Ronald Reagan. President George H.W. Bush appointed him as Secretary of State and later as White House Chief of Staff. He is a Trustee of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation.

James Baker was interviewed for the Gerald R. Ford Oral History Project on November 2, 2010 by Richard Norton Smith.

Smith: First question. Was the Ford White House slow to wake up to the Reagan threat, both that Reagan might in fact run and that he would be as formidable an opponent as he was?

Baker: Well, I don’t think they were slow. Then, of course, I was not in the Ford White House. I was Undersecretary of Commerce.

Smith: Who was Secretary at that point?

Baker: When I went up there, it was Rodgers Morton who ended up being Chairman of the President Ford Committee. After President Ford asked him to go over and chair the committee, he appointed Elliott Richardson as Secretary of Commerce. So, I worked under both Morton and Richardson, but for almost three or four months, I was the acting Secretary of Commerce, the interregnum between the time that Rog left and Elliott came in.

Smith: As you imagine, there’s been a lot of overlap with Nixon and Watergate in this project and a number of people who have characterized Elliott Richardson – and some of those, surprisingly to me, have emphasized his presidential ambitions.

Baker: I wrote in my book, Richard, that Elliott was a Boston Brehmin and he was very cerebral. So cerebral to the point that sometimes his writings were so esoteric, you couldn’t really understand them. And I have the fondest regard and affection for Elliott, but he was a politician, too. And he enjoyed running for office, he enjoyed campaigning. He was a bit formal.

Smith: Nelson Rockefeller, as vice president, said to someone, “Elliott Richardson’s so stuffy that when he’s in the room, you can’t breathe.”

Baker: Well, that’s the impression he gave to people, but I think if Elliott liked you, he would not come across as being stuffy. But, to people he didn’t know well, or that he might have thought less of, he probably did.

Smith: Do you think he saw himself as a president?

Baker: Oh, sure. I think he was very much of the view that he could’ve done it. I don’t think that he was very realistic in thinking that, given the make-up of the Republican Party at that time and the imperative of getting the nomination before you run for president.

Smith: Rogers Morton took some heat for the performance of the campaign. Was that unfair?

Baker: Yes, I think largely unfair. A lot of it resulted from an unfortunate photograph that was published, if I’m not mistaken, on the front page of the Washington Times where they’d asked him some question about the campaign and he said, “Look, I didn’t come over here to be the captain of the Titanic” or something like that.

Smith: “To rearrange—“

Baker: “To rearrange the deckchairs on the Titanic.” And, in the background, there were liquor bottles because we would celebrate each primary after it was over, so we’d celebrate the ones we could and commiserate on the ones we couldn’t. But Rog ran a good campaign in my view. I mean, he really did. Those stories, I think, is one reason they opted to make me Chairman of the President Ford Committee. I mean, that was one of the reasons, but the real reason, I think, is Rogers was sick with cancer. He had prostate cancer and he had it pretty severely.

Smith: Did Ronald Reagan’s challenge ultimately make Gerald Ford a better candidate? Which is not the same as saying whether it helped him or hurt him in November.

Baker: I think you could argue that it might have, yes. It might have. It certainly meant that he had to spend more time campaigning. And, you know, a lot of people have written that Ronald Reagan was a master when the red light came on the camera and that Jerry Ford would freeze up when the red light came on the camera. And it wasn’t that Jerry Ford would freeze up, in my opinion, it was simply that he was thinking about what he was going to say. But there was always a short pause between the question and the answer. And it gave the appearance that maybe he wasn’t entirely sure. If you read my book, you saw where I quoted Stu Spencer in there as being very straight with everybody – and at one point he said something to the effect that, “Just because you’re no fucking good, Mr. President,” or something like that. And the beauty about Jerry Ford, who was just a marvelous human being, a wonderful person, is he would laugh at that and say, “Well, that may be right, but I’m getting better.” But he became a damn good candidate, I think. I thought he was an extraordinarily good candidate. Look where he came from in the general election, twenty-five points behind in August and dead even on election day. Lost by only 10,000 votes out of 81 million votes that were cast. You’d turn 10,000 votes around in Ohio and Hawaii and Ford would’ve been elected.

Smith: Does that fit into the larger trajectory? Ford supposedly said that what really hurt was losing the job just when felt he’d mastered it. And one way of looking at Ford’s two and a half years is as someone who came into the office, to which he’d never aspired, who had a congressional mindset, congressional skill set, and who had to learn – not unlearn those talents, but learn executive talents, learn communications, learn what it means to be president. Did he grow into that job?

Baker: Absolutely. I think that’s absolutely correct. He had never had any real executive experience. I can’t remember when he was first elected.

Smith: ’48.

Baker: ’48. So, he’d been a legislator for many, many years, which is one reason he was such a good consensus politician, I think. But he had to learn executive skills and he did so and did so very, very well.

Smith: When did you come on to the PFC?

Baker: I came to Washington in August of ’75. Rog Morton, when he was moved from Interior – which he didn’t want to do – to Commerce, he wanted his own deputy. And I’m sure that George Bush, who at the time was in Beijing as our representative there, suggested my name and so did some other people down there in Texas who’d been helpful in Republican politics. And I interviewed with Rog and he decided I was the person he wanted. Don Rumsfeld was the White House Chief of Staff at the time. They were concerned about the Reagan challenge. They certainly were concerned about it in May or June of ’75. And Ford had only been there less than a year at that point. Rummy wanted to appoint Bill Banowski who had been the president of Pepperdine University and was national committeeman from California – a close Reagan associate – with the idea that that might…you know. But they also offered Reagan, if you know your history, they also offered him a job as Secretary of Commerce and one other position in the cabinet, which he turned down.

Smith: I think it was Secretary of Transportation.

Baker: Well, it may be. I don’t know the answer.

Smith: Something improbable.

Baker: Anyway, I came in August of ’75, became Undersecretary of Commerce and it was in late April and I went on a campaign trip to Texas. I was one of the few Texans in the administration. And I went on the campaign trip to Texas with President Ford and on the way back, he asked me to go over to the PFC, the President Ford Committee, to become the delegate hunter in the nomination fight with Ronald Reagan. And that was because his delegate hunter had been killed in an automobile accident.

Smith: Jack Stiles.

Baker: Jack Stiles.

Smith: Nelson Rockefeller went to his grave convinced that Don Rumsfeld did him in and that he also deep-sixed George Bush to the CIA. But also, Rocky didn’t age well. He had convinced himself that Jack Stile’s death was not accidental.

Baker: Oh really?

Smith: Yeah, literally. He thought Bill Colby was a Soviet agent. I mean, he had this kind of paranoia.

Baker: Well, what would he think would be the motive in getting rid of Stiles? He was just a personal friend of the president.

Smith: Exactly. But he’d convinced himself that there were people around the president who didn’t want to see him reelected. I’ll leave it at that. It’s pretty far-fetched.

Baker: I find that bizarre.

Smith: Yeah. But, April is a critical moment because they’d won New Hampshire and they’d won Florida. They seemed to be on a roll, but its pre-North Carolina and Texas.

Baker: Just barely pre-North Carolina.

Smith: Okay.

Baker: If it was pre-. I’m not sure whether it was pre-North Carolina. North Carolina is where the Reagan campaign dug themselves back into the race, actually. And then you had Missouri and Texas and I remember shortly after being sent over to the PFC, I went to Missouri with the president and we lost all but three delegates and they were governor and some of the others. Then we went to Texas and we lost 100 to nothing, including John Tower, the only Republican who’d been elected state-wide in Texas since Reconstruction. And they wouldn’t let him be a delegate, wouldn’t let him have a seat. I mean, it was a blood bath.

Smith: Was there resentment because John Connally withheld his endorsement in that contest? I think he harbored some vice presidential aspirations; at least that’s what we’ve been told.

Baker: I don’t know the answer to that. I don’t remember. When we had Connally, as a Texan, I was sort of put in charge of him and, if I’d been Chairman of the PFC, I wouldn’t have been doing that. This was probably when I was the Deputy Chairman for Delegate Operations. But I don’t know the answer to that. I can’t remember. That was thirty years ago.

Smith: As Chief Delegate Hunter, what could you offer people besides intellectual arguments about the president? We’ve been told, for example, that the dinner for Queen Elizabeth was full of uncommitted Republican delegates.

Baker: It wasn’t full, I may be mistaken, but I believe I took an uncommitted delegate to dinner. We would take uncommitted delegates to White House dinners. I remember we gave some uncommitted delegates tickets to the ships…

Smith: Oh, the tall ships?

Baker: The tall ships. Well, with the anniversary—

Smith: With the Bicentennial. Fourth of July.

Baker: Bicentennial. Yeah, that’s right. But we were very careful. Extraordinarily careful. You’ve got to remember that we were running this campaign in the immediate aftermath of Watergate, where we’d been wiped out and we had an overwhelmingly Democratic Congress that was prepared to investigate anything and everything that happened. And, man, we crossed the Ts and dotted the Is. I kept a log, a memo, of every solicitation that came to us from an uncommitted delegate or prospective delegate that was improper. These delegates would say, “Well, look, I’ll vote for Ford, but I want to be on the Federal Communications Commission” or “I want to be on the Federal Trade Commission.” We would enter all that just to make a record – just to show that we wouldn’t entertain that.

Smith: We heard about a family – I want to say from New York, not Manhattan, but from the Bronx or Queens or something – supposedly some woman who kept going back and forth and was finally called and asked, “What would it take to nail you down?” And she wanted to bring her family into the Oval Office to meet the president. I guess it was a pretty scruffy looking group.

Baker: That’s perfectly permissible.

Smith: Oh, sure.

Baker: I mean legal. Totally legal. Had we been met with a request like that, we would’ve tried to arrange it. On the other hand, if she’d wanted an appointment for something for herself or somebody in her family or something that is inappropriate, we would write it down so we had a record.

Smith: Were you surprised by anything in the course of that, just in terms of what people expected, what they wanted?

Baker: Well, I think we had a fairly substantial number of requests that were inappropriate and that’s why we kept that log and kept a record of it. But it was a fascinating experience for this reason: It was the last really contested convention in the history of either of the two major parties. ’76 in Kansas City was the last time it went to the floor. The nomination, that is. The last time a presidential nomination went to the floor of a convention. And we didn’t know, we weren’t sure, from day to day whether we would win or not. I’ve written about this, as you know, and I’ve said that I never could understand why the Reaganites, instead of doing – what was it? About naming your vice president in advance and they named Schweiker.

Smith: An unemotional, bloodless procedural issue.

Baker: Yeah, it was a technical, procedural thing. Why didn’t they come with a platform that said, “Fire Kissinger”? That would’ve really grabbed a hold of some of these people.

Smith: You’d think they’d try to have it both ways. I mean, you very shrewdly gave way on the foreign policy plank.

Baker: The 14-C, wasn’t it?

Smith: It’s interesting because Stu Spencer agrees with you. He thought Sears made a fundamental mistake in putting so many eggs in the basket of a procedural issue. As opposed to going after the emotional issue of foreign policy.

Baker: That’s correct.

Smith: Now, he got the foreign policy plank because, in effect, you rolled over.

Baker: We would not let that become an issue because we were fearful, and I think rightly so, that we would lose enough delegates. It was a pretty close contest, as you know.

Smith: Right.

Baker: I think we only won by 100+, maybe 105 or so delegates out of 3,000 on the floor.

Smith: And Tom Korologos tells the story that Kissinger was more than slightly miffed and wanted to put up a fight and I don’t think grasped—

Baker: And so did Rocky.

Smith: And Rocky, yeah. And Kissinger in one of his patented threats to resign and Tom says, “If you’re going to quit, Henry, do it now. We need the votes.”

Baker: Who said that?

Smith: Tom Korologos.

Baker: Korologos. “If you’re going to quit, do it now.”

Smith: You can see Korologos saying that.

Baker: Yeah. “Henry, if you’re going to quit, do it now.”

Smith: Yeah.

Baker: Well, you know the flap I got in, too, by announcing Kissinger’s retirement from the Ford administration. If you read my book, the second one I wrote, not the one about being Secretary of State. But I wrote a book – you’d enjoy it because it’s a political book – Work Hard, Study, and Keep Out of Politics, which was my grandfather’s mantra. So I entitled the book that. But, in that, I write about having been sent to Oklahoma as a lowly Undersecretary of Commerce to raise some money during the primary. And I got to the home of a banker down there and it’s a nice, quiet little group of check writers around the pool and I’m told there’s no press in attendance. So, I give my little pitch and then take questions. And one of the questions was, “Will Henry Kissinger be in the second Ford administration?” I said, “I can’t conceive of that happening.” Well, it turns out there was a stringer for the Daily Oklahoman, the college paper there, and he wrote this stuff.

By the time I got back to Washington, it was on the wires. And I went to a ceremony in the Rose Garden and on the way out, Nell Yates, the president’s secretary, came by to see me and said, “Before you go back to Commerce, stop off and see Mr. Cheney in the Chief of Staff’s office.” I went in there and Dick’s sitting there and said, “I understand you announced Henry’s resignation.” I said, “What are you talking about?” He said, “Well, that’s what the press is saying.” I said, “Oh, that couldn’t be. There must be some mistake.” He said, “Look, don’t worry about it. Just go back and make it right with Henry.” So, I went back to Commerce, called the Secretary of State, who was a more than imposing figure in that administration, and groveled my apologies, which he was reluctant to accept. He’d never met me before. Three or four days later, I went to an event over at the State Department, I go through the line, and I introduce myself to him. He says, “Oh, you’re the guy that announced my retirement.” A lot of interesting memories from those times.

Smith: We talked to Peter McPherson. Interesting. He said his recollection of what really fueled the Reagan challenge in the months leading up to its formal announcement – one was the refusal to meet Solzhenitsyn, and the other was the common situs picketing legislation.

Baker: Peter was my Deputy. He’s a man of great talent and he was President of Michigan State. He was head of AID. I have great respect for Peter, but the common situs picketing issue would’ve operated the other way. That’s really where I think I first became noticed by the Ford White House because I was the acting Secretary of Commerce when all that came up and I argued in the Economic Policy Board that President Ford should veto that bill. And there were a lot of people arguing that he should sign it, including John Dunlop, the Secretary of Labor – because Ford had indicated when it was first introduced that he would be inclined to sign it. Dunlop resigned, but I really made a big stink and the Economic Policy Board sent a memo to the White House saying, if you do this, you’re really going to make it awfully hard to get the nomination over a Reagan challenge. And he vetoed it and Dunlop quit. So, how can Peter say common situs picketing?

Smith: He may have thought leading up to the veto…

Baker: Well, having supported it initially, not saying from the very start, we can’t live with this.

Smith: And the sense that it was an administration initiative.

Baker: Well, that may be. Common situs picketing would’ve been anathema to any conservative.

Smith: Explain the issue briefly. Why is it such a hot button?

Baker: It was illegal then for a labor union to go on a site when they have a grievance with one employer and picket that site and then have their picketing apply to all the other unions at the workplace. In other words, if one union had a dispute at a site, this legislation would’ve made it legal for them all to strike. I think that’s what it is.

Smith: So, you can certainly understand why it would be out there.

Baker: Anyway, I do remember that it was just an anathema and here I was, a conservative Republican from Texas and the debate on this in the Economic Policy Board was scary to me because I thought, “Boy, if we do this…” This was very much anti-Right-to-Work and so forth and so on.

Smith: Yeah. Did you have much contact with Bob Hartmann?

Baker: I did not have much, no.

Smith: Generally, how bitter was that convention in ’76?

Baker: I think it was very, very bitter.

Smith: Remember the dueling entrances by the candidates’ wives?

Baker: Well, you look at what I just told you about the Texas delegation. They wouldn’t let the sitting senator – the only Republican ever elected statewide in Texas since Reconstruction –wouldn’t let him go as a delegate. It was a tough deal.

Smith: And presumably that spilled over into the vice presidential selection process. I mean, all these years later, there are still people who will tell you differing versions of what Reagan did or did not impart. The overwhelming evidence we have is that the Reagan camp, beginning with the candidate himself made it crystal clear that he did not want to be asked to be on the ticket; indeed, made that a condition of their getting together subsequently.

Baker: Well, the Reagan camp did, but you really must get this book, because I write about it in one chapter of this book in detail. Here I am, the White House Chief of Staff for Ronald Reagan and I’m sitting in the Oval Office – just the two of us – and I said, “You know, Mr. President, if President Ford had asked you to run with him and you’d agreed, you would probably never have been president.” And he said, “Well, Jim, that may be so, but if he’d asked me, I would’ve felt duty bound to run.” I’ve got this all. You’ll find that fascinating. But, what I think, and he certainly wasn’t lying to me. He didn’t do that. That’s not the way Ronald Reagan was. But I know that his campaign came and said, “We will have the unity meeting provided you don’t ask the Governor to be a vice president.” Well, that’s all Ford needed. He didn’t want to ask him to be vice president. He didn’t want to ask him and Reagan didn’t want to be asked.

Smith: Well, then, let me jump ahead, because there’s this bizarre sequel in 1980. Again, people are still debating over whether it was ever real. There are some people who think it was kind of a show on the part of the Reagan people.

Baker: No, I think it was real.

Smith: You think it was real?

Baker: I think it was real and I was not a Reagan person then. I was a George H. W. Bush person. And, interesting, I’d been President Ford’s campaign chairman in ’76. Before I signed on with George Bush in ’88, we went to see President Ford. I went to see him to say, “Mr. President, is this going to be okay with you?” And George went to tell him he was going to run to show him the courtesy as the former president. So, we called on him out there in California. Interestingly enough, I flew into the convention from Omaha, Nebraska, where I’d been at a board meeting for Dick Herman’s company. Dick Herman was a national committeeman from Nebraska. Close friend of both George Bush and Jerry Ford. And I flew from Omaha in Jerry Ford’s plane because he happened to be there and they were talking about all this stuff on the way in. But I know from a fact from talking to the Reagan people that I worked with that it was very real. But it would never have worked, Richard. I mean, again, I wrote in the book, I said to President Reagan, “Mr. President, how would we have addressed President Ford? Would we have addressed him as ‘Mr. President/Vice President’ or ‘Mr. Vice President/President?’”

Smith: Yeah.

Baker: It never would’ve worked and they both came to that conclusion after awhile. I think one of the conditions he put down was he wanted also to be White House Chief of Staff and Vice President and maybe there was another one. I can’t remember.

Smith: Actually, he got that idea from Nelson Rockefeller, who toyed with the idea in ’76 of going back on the ticket, but only if he could be Chief of Staff because he had decided that that was the role that a vice president could constructively play.

Baker: But he couldn’t have gone back on the ticket because President Ford had asked him to step down.

Smith: Right.

Baker: Isn’t that your understanding?

Smith: It is, yeah.

Baker: And you want to know what I think? I want to tell you something I think. I think that was a terrible mistake as it turned out. The campaign was so close that I think if he had kept Rockefeller on, I think he still would’ve gotten the nomination.

Smith: You do?

Baker: I do. And I think we would’ve won the election. And I think if he’d had Reagan on there, we clearly would’ve won the election.

Smith: Presumably, the Schweiker pick was designed to bring Drew Lewis and the Pennsylvania delegation to Reagan.

Baker: That’s correct.

Smith: Was that a hope? Was it based on something more than just a hope? Did they have reason to believe?

Baker: You’d have to ask John Sears that. I don’t know whether they had more than reasonable hope, but there was never any question, from our standpoint. I mean, Drew said, “I’ve committed. I’ve been here. I’m going to be here.” And he was. So, it not only didn’t work, I think it sort of backfired on him a little bit.

Smith: Well, it took some of the purity out of it. I mean, it made it easier for people like Clark Reed, I imagine, in the end to go with Ford.

Baker: Probably did. Reed and perhaps some others, some of the uncommitted.

Smith: After the convention, the acceptance speech which everyone agrees was probably the best speech Ford ever gave and his challenge to Carter to debate – did that begin the process of at least shifting the dynamics of that race? Taking the offensive?

Baker: Well, if you’re asking me if I think that was a successful campaign strategy, I do. I think he had to do something to shake it up. As I told you, when I took over as Chairman of the President Ford Committee, we were 25 points behind. That was in August. It was there at that session in Vail where I think he threw the challenge out. Here’s a sitting and incumbent president saying, “I want to challenge…”

Smith: I’ll never forget hearing Mark Shields, who was not a Republican partisan, talk about what a great campaign Ford ran and in particular how good the media was. You had Bailey-Deardorff?

Baker: Bailey – Deardorff did a great job.

Smith: And probably the last jingle that people remember…“I’m feeling good about America.” The man on the street interviews. I mean, the whole package.

Baker: The whole thing was good and how about the Joe & Jerry Show? With Joe Garagiola.

Smith: Yeah, where did that come from?

Baker: Well, they hit it off.

Smith: Just chemistry?

Baker: Well, yeah. They were cutting one spot if I’m not mistaken and they hit it off so well and it was so entertaining, they decided, “We’d better do more of these.” And they were very successful.

Smith: And Pearl Bailey was also in there. I remember the election eve broadcast was from Air Force One and you had Joe Garagiola and Pearl Bailey. Interesting mix.

Baker: And President Ford couldn’t speak. His voice had gone.

Smith: At the end – we talk about Ohio. He went back to Grand Rapids and had a very sentimental homecoming. Might he have gone to Ohio instead? Was there a debate at the end of the campaign about where to send him?

Baker: I don’t recall there being any debate at that time, but let me tell you something. Nobody ever worked any harder than he did in that campaign. And, as I say, on the last day, he couldn’t speak. I don’t recall an argument about whether we should stop off in Ohio on the way home to Michigan.

Smith: Yeah, basically.

Baker: I don’t recall that.

Smith: The moment you heard the Polish gaffe, did you know that you had a problem?

Baker: Yeah, we did. And, again, I write about this in detail in my book. Henry called the president after the debate and said, “Mr. President, you did a wonderful job. Marvelous. Really terrific.” And so it was really hard to get the president to go out there and say, “Yeah, this was a mistake” or say, “I misspoke and here’s what I meant by that.” That’s what we were trying to get him to do and it was hard. Kissinger’s going to take a trip to Africa. Kissinger was the bete noir of the conservatives. And before going to Africa, they wanted him to come into the White House – this was just before Texas, so I was still at Commerce – they wanted him to come into the press room and brief about his trip at the White House

And I called Dick on the phone and I said, “Dick, you’re not really going to do this, are you, just in advance of the Texas primary?” He said, “Look, I’ve tried to turn the old man around on this and I broke my pick. Now, if you want to come over here and try, you’re welcome to.” I said, “I do.” So, I came over there and I think by that time he’d already asked me to become the delegate hunter, so I had a little more leverage than just the Deputy Secretary at Commerce. So, I went in, Dick and I, and we sat there. I remember saying, “Mr. President, this would be very detrimental in the southern states and particularly in Texas. Why don’t you just let him go do the trip? Why do you have to have a big, splashy press conference beforehand?” And the president’s sitting there going puff, puff – you know, he always puffed on that pipe – he said, “Well, Jim, Henry’s doing a remarkable job and I think he ought to tell the American people about it.” And he said, “And, anyway, the thinking Republicans in Texas will understand.” I said, “Mr. President, there are no thinking Republicans in Texas on this issue.”

Smith: We’ve established he was stubborn. Did you ever see his temper?

Baker: Who? President Ford?

Smith: Yeah.

Baker: Not too much. You know, I saw Reagan’s because I was his Chief of Staff for four years and two weeks and he had one, too. You didn’t see it often, but you could see it. I don’t recall ever seeing Ford just really lash out at someone.

Smith: At the end of the campaign, did you think you’d caught up? Did you think you really had a good chance to win?

Baker: We knew the Gallup was even going into Election Day. And then we knew we started getting the exit polls and they didn’t look real good. We went over to share them with the president at 4:30, 5:00 o’clock in the Oval Office. I remember going over with Teeter and maybe Stu, Teeter and Stu and I and maybe Dick. And the president didn’t seem to be too upset about that. He said, “Well, those are just exit polls.” But we were very hopeful because the Gallup was even and then we got the bad news of the exit polls, but we still lost so very narrowly. I remember thinking to myself at 3:00 o’clock in the morning, the morning after Election Day, “This is the most bizarre thing in the world. Seven years ago, I was a Democratic lawyer in Houston, Texas, and now I have run a campaign or been chairman of campaign for an incumbent Republican president in the closest presidential election of my lifetime.” Well, guess what? If you remember what happened in Florida in 2000, you know it wasn’t the closest presidential election of my lifetime. But it was very bizarre because he came from so far back.

Smith: Did Texas hurt especially? I mean, was he counting on Texas?

Baker: Not after—

Smith: Not after the primary?

Baker: Well, Texas was a big passel of electoral votes.

Smith: I think we’ve been told that Connally assured him as late as Election Day that it was in the bag.

Baker: I think Connally was very confident that we would carry it and we didn’t. But, I mean, had we done it, we’d win. You know, it almost would’ve done it in the Electoral College. It would’ve flipped Ohio and Hawaii.

Smith: Did you see him later that night? Were you at the White House?

Baker: No, I was at the election headquarters downtown and I had to do the press stuff down there. As I say, it wasn’t until 3:00 o’clock in the morning. I was in communication with the White House, but I wasn’t over there.

Smith: Did it take him awhile to bounce back? We’ve heard that.

Baker: You know, I’m not the best one to answer that because when the campaign was over, I only saw him two or three times after that while he was still president.

Smith: He went around and told some people, “I can’t believe I lost to a peanut farmer.”

Baker: Then they became fairly good friends.

Smith: They did. I’ve sometimes wondered if one of the things that brought them together was the fact that they’d both run against Ronald Reagan.

Baker: That’s true. That is. Absolutely. And they both in effect lost to Ronald Reagan, although President Ford didn’t lose to him, but that challenge damn well hurt us. I mean, you can make the argument that he became a better campaigner and I think he did, but the challenge hurt.

Smith: Next to last thing and maybe it’s awkward, but there’s no shortage of people who say that if Governor Reagan had done more in the fall campaign in places like Mississippi and maybe Ohio that it could’ve spelled the difference. What’s your take?

Baker: You know, I’ve lead or helped lead five presidential campaigns and every damn one of them you can go back and find this or this or this or any number of things that would’ve made a difference. You can argue that if Governor Reagan had been more active, it might’ve helped, rather than just being supportive of the cause and the effort. Who’s to say? But that was probably as bitter a primary as either party has experienced in many, many moons. So, it’s pretty hard to say. As you say, sensitive for me because I love both of them, I was privileged to work for both of them and privileged to work for George 41, as well. And, you know, I tell people I’m the luckiest guy in the world because I got to work directly for three wonderful men, wonderful characters, and beautiful human beings. All three of them. And then got to serve another one as a private citizen in various capacities.

Smith: In the Reagan White House were there lingering resentments toward Ford? I don’t mean at the top.

Baker: No. In our White House?

Smith: Yeah.

Baker: No. Now, I’m not aware that he felt that way. I really am not. And I never heard it from anybody.

Smith: Certainly in terms of President Reagan himself.

Baker: No, no, no, no. You know, President Reagan is completely without guile. I mean, in fact, some people would take advantage of him. He believes the best about people. But I never noticed any animus toward President Ford in the Reagan White House.

Baker: Well, he came to the Baker Institute, at the groundbreaking ceremony we had for my institute at Rice University. Showed up there with George H. W. and we had Carter and Reagan by television. So, President Ford was there. I used to call him every time I’d go out to California in the desert and go by and see him. But that was the only way I saw him.

Smith: Did he express concern about the direction the Republican Party was going?

Baker: Yes. He had the view that the party was moving too far, too fast to the Right.

Smith: Particularly on social issues?

Baker: Yeah, I don’t know that he said particularly on social issues, but generally speaking. But, you know, I didn’t have that many conversations with him after he left office where we would talk about that. We’d talk about other things, but we didn’t talk about that.

Smith: Were you surprised by the amount of reaction when he passed away? Because, you know, he’d been out of the public eye for awhile. And it almost grew as the week went along.

Baker: You know something? He was the right man for the country at the time and he restored our pride and confidence in ourselves and he made the hard decisions. He would veto bills that were bad policy and, as you say, he pardoned Nixon and, boy, didn’t we see that every day in the campaign. It cropped up every day.

Smith: Do you think it was a significant factor contributing to his defeat?

Baker: Absolutely a significant factor. Huge. But people loved him and that’s what you saw with the accolades that poured in after he passed away. And I’m still on the Board of the Ford Foundation and I interface every now and then with Jack and Susan and Steve. Betty, of course, is frail right now, but still pretty good upstairs.

Smith: Last thing: how do you think he should be remembered?

Baker: Well, I think, as I said, I think he was the right man for America at a very, very difficult time in our history. I don’t know many people who could’ve come in and done it with the class that he did it. And, you know, people could disagree with Jerry Ford, but nobody could dislike him. He had a wonderful ability, he was a consensus politician. He could reach across the aisle. That’d come from his years of legislative experience up there, many of which were as Minority Leader. But I think that I’d answer by simply saying he was just a beautiful human being and I think that people now recognize that and they recognize he was the right person at a very difficult time for America. That was a terribly difficult time.

Smith: People tend to forget. I mean, we’re always in the crisis of the moment, but imagine someone coming in with so many problems and without the legitimacy of an election.

Baker: Of an election, that’s right.

Smith: Without a transition period.

Baker: That’s right. No transition. And not elected. The only unelected president, probably, we’ll ever have.

Smith: And presumably that made it all the more important for him to win that ’76 race.

Baker: That’s right. Yeah. And to come so close from so far back. Really close. Those kinds of defeats sometimes hurt more than the wipeout losses.

Smith: Last thing and then I promise we’ll let you go. Tell us about his intelligence.

Baker: I think President Ford was extraordinarily intelligent. I’ve already said that he didn’t come across that way on television because I think he would always stop and think about his answer. The question would come and there would be a pause. But he was a Phi Beta Kappa, right? Am I wrong about that? I think I’m right about that.

Smith: I think you’re right.

Baker: And, you’re bound to have a fair amount of intelligence if you graduate Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Michigan.

Smith: And the last president to introduce his own budget. Remember? To brief his own budget in front of the press.

Baker: That’s correct.

Smith: Because he knew every line on that budget.

Baker: He knew that stuff. Well, he knew that from his years of serving in the legislature, but he knew the intricacies of government from the legislative standpoint, not as much from the executive. But since the Congress are the ones that deal with the budget, the Congress appropriates and so forth, he knew that backwards and forwards. Well, what do you think would’ve been different if he had won?

Smith: I think there’d be a Truman-esque aura around Ford. Ford and Truman had a lot of similar qualities. They were plain-spoken. They weren’t flashy – Midwestern, straight shooter – and I think that would’ve made more of an imprint on the country, obviously, given another four years and the legitimacy of an election. In terms of specific policies, who knows? I mean, presumably the Panama Canal Treaty would’ve gone forward. It’d been put off because of the Reagan challenge.

Baker: Yeah, but politically it would’ve been a cataclysmic event. You would not have had pictures of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush or George W. Bush in the White House. I mean, it would’ve been totally different.

Smith: But you might also not have had pictures of American hostage in Tehran.

Baker: That’s right. There would’ve been a lot of substantive things as well. I’m just talking about on the politics side.

Smith: Yeah, you’re right.

Baker: If he had won that election, he could’ve then run for another term and then Ronald Reagan might not have been president. George Bush would not have been vice president and then president. And then George W. would not have…

Smith: That’s a perfect note on which to end. Thank you.